Living with shikai: generalized anxiety disorder in kendo

To retain heijoshin (an even mind) is one of the greater goals in kendo.

“Heijoshin reflects a calm state of mind, despite disturbing changes around you. [It] is the state of mind one has to strive for, in contrast to shikai, or the 4 states of mind to avoid:

- Kyo: surprise, wonder

- Ku: fear

- Gi: doubt

- Waku: confusion, perplexity“

(Buyens, 2012)

In the following pages I would like to introduce you to generalized anxiety disorder, hereafter “GAD”. For sufferers of GAD every day is filled with two of these shikai: fear and doubt. While I am but a layman I do hope that my personal experiences will be of use to those dealing with anxiety disorders in the dojo. I will start off by explaining the medical background of GAD, followed by my personal experiences. I will finish the article by providing suggestions to students and teachers dealing with anxiety in the dojo.

Anxiety disorders: definition and treatment

All of us are familiar with anxiety and fear as they are basic functions of the human body. You are startled by a loud noise, you jump away from a snapping dog and you feel the pressure exuded by your opponent in shiai. They prepare your body for what is called the “fight or flight” reaction: either you run for your life, or you stand your ground and fight tooth and nail. These instincts become problematic if they emerge without any reasonable stimulus. The most famous type of such a disorder are phobias, the fear of specific objects or situations, which are suggested to occur in ~25% of the adult US population. (Rowney, Hermida, Malone, 2012)

Other types of anxiety disorders are:

- Acute Stress Disorder

- Agoraphobia

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder [GAD]

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder [OCD]

- Panic Disorder

- Post-traumatic Stress Disorder [PTSD]

For the remainder of this article I will focus on the disorder with which I have personal experience: generalized anxiety disorder.

Perhaps the easiest ways to describe GAD is to use an analogy: GAD is to worry, as depression is to “feeling down”. Just like a depressed person cannot “simply get over it” and is debilitated in his daily life, so does a person with GAD live with constant worry. As it was described by comic artist Mike Krahulik:

“The medication I picked up today said it could cause dizziness. […] I had to obsess over it all afternoon: I drove to work today by myself, will I be able to drive home? What if I can’t? How will I know if I can’t? Should I call the doctor if I get dizzy? How dizzy is too dizzy? What if the doctor isn’t there? Will I need to go to the hospital? Should I get a ride home? I can’t leave my car here overnight. The garage closes at 6 what will I do with my car? What if Kara can’t come get me? Should I ask Kiko for a ride home? If I get dizzy does that mean it’s working? Does that mean it’s not working? What if it doesn’t work?” (Krahulik, 2008)

Paraphrased from DSM-IV-TR (footnote 1) and from Rowney, Hermida, Malone, criteria for GAD are that the person has trouble controlling worries and is anxious about a variety of events, more than 50% of the time, for a duration of at least 6 months. These worries must not be tied to a specific anxiety or phobia and must not be tied to substance abuse. The person exhibits at least three of the following symptoms: restlessness, exhaustion, difficulty concentrating, irritability, muscle tension and sleep disturbance.

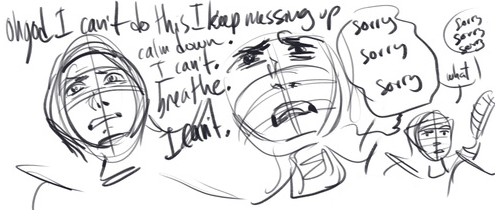

Thus the symptoms differ per person, as does the potency of an episode. In severe cases of GAD episodes will result in what is known as a panic attack, which you could describe as a ten-minute bout of super-fear. Effects of a panic attack may include palpitations, cold sweat, spasms and cramps, dizziness, confusion, aggressiveness and hyperventilation. Because of these effects, people having a panic attack may think they are having a heart attack or that they are going plain crazy.

An important element to GAD is the vicious cycle or snowball effect. As my therapy workbook describes it (Boeijen, 2007), a sense of anxiety will lead to physical and mental expressions, which in turn will lead to anxious thinking. People with GAD will often fear the effects of anxiety, like fainting or throwing up. These anxious thoughts will create new anxiety, which may worsen the experienced effects, which in turn will feed more anxious thoughts. And so on. Thus, even the smallest worry could start an episode of anxiety, like a snowball rolling down a slope. What may get started with “The fish I had for lunch tasted a bit off.” may end up with “Oh no, I’m having a heart attack!“. If that doesn’t sound logical to you, you’re right! The vicious cycle feeds off of assumptions, worries and thoughts that get strung together. I’ll have two personal examples later.

Treatment of GAD occurs in different ways, often combined:

- Medical treatment of pre-existing physical ailments or other disorders.

- Medicinal treatment of the anxiety, with for example Prozac, Zoloft, Valium or Ativan.

- Psychotherapy.

- Support structures through the education of family and friends.

All sources agree that having proper support structures is imperative for those suffering from any anxiety disorder. Knowing that people understand what you are going through provides a base level of confidence, a foothold if you will. Knowing that these people will be able to catch you if you fall is a big comfort. Having someone to help you dispel illogical and runaway worries is invaluable.

My personal experiences with GAD

I am lucky that I suffer from mild GAD and that I have only experienced less than fifteen panic attacks in my life. Where others are harrowed by constant anxiety, I only have trouble in certain situations. I was never diagnosed as such, but in retrospect I have had GAD since my early childhood. At the time, the various symptoms were classified as “school sickness”, irritable bowel syndrome and work-related stress. It was only during a holiday abroad in 2010 that I realized something bigger was at hand, because I had a huge panic attack. I was extremely agitated, could not form a coherent strain of thought and was very argumentative. My conclusion at the time was that “I’m going crazy here, that has to be it. I really don’t want this, I need a pill to take this away right now!“. Oddly, I discounted the whole thing when we arrived home. It took a second, big panic attack for me to accept that I needed to talk to a professional.

This second panic attack progressed as follows:

- 13:10: Go outside to run an errand in a part of town I’m not familiar with.

- 13:11: “I wonder how my daughter is doing, with her gastric enteritis.“

- 13:12: My stomach rumbles noticeably.

- 13:13: “Gee, it’d suck if I got infected with enteritis as well.“

- 13:15: “Wait, what if I already am? I wouldn’t want to getunwell on my errand!“

- 13:20: “Crap, this place is further than I thought. I thought it was close by!“

- 13:21: I start feeling apprehensive and queasy.

- 13:22: “Maybe I should turn back. I think I’m panicking. No I need to conquer this!“

- 13:25: I get to the shop and place my order.

- 13:27: My panic gets heavier as the order takes very long. I am now having stomach cramps.

- 13:28: Being denied access to the shop’s lavatory I start hyperventilating. I crouch to feel safer.

- 13:30: Having paid I quickly leave. The thud of the door takes a load of my shoulders.

- 13:33: I’m feeling relieved, but still have cramps.

- 13:50: I arrive back at the office and feel exhausted and shaky but the panic is over.”

(Sluyter, 2011)

This illustrates the aforementioned vicious cycle: an innocuous thought (“I wonder how my daughter is doing.“) leads to me worrying that I’m ill, which leads to me worrying about my errand, which gives me stomach cramps, which reinforces my fears about being ill, which makes me nauseous and dizzy, and so on. Worries express themselves, which creates anxiety, which in turn reinforces the earlier worries. It didn’t take my doctor long to refer me to a therapist for Cognitive Behavior Therapy, hereafter “CBT”.

CBT is one of many forms of therapy applicable to anxiety disorders and it is often cited as the most effective one. It is suggested (Rowney, Hermida, Malone, 2012) that CBT achieves “a 78% response rate in panic disorder patients who have committed to 12 to 15 weeks of therapy“. In my personal opinion CBT is successful because it is based on empowerment: the patient is educated about his disorder, showing him that it does not have actual power over him and how he can deal with it. As part of therapy, one learns to recognize the patterns that are involved in the disorder and how to pause or halt these cycles. Patients are given tools to prevent episodes, or to relax during an attack. CBT also relies upon the notion of ‘exposure’ wherein the patient is continuously challenged to overstep his own boundaries. The senses of self-worth and of confidence are improved by realizing that your world isn’t as small as you let your fears make it.

I have learned that the best way to deal with a runaway snowball of thoughts is to dispel the thoughts the moment they occur. Anxious thoughts often start out small and then spiral into nonsensical and unreasonable worries. By tackling each question when it comes, I maintain a feeling of control. Having someone with me to talk over all these worries is very useful, because they are an objective party: they can answer my questions from a grounded perspective. My wife has proven to be indispensable, simply by talking me down from the nonsense in my head.

I first started kendo in January of 2011, half a year before I started CBT. In the week leading up to class I devoured online resources, just so I wouldn’t make a fool of myself. In my mind I had this image that I would be under constant scrutiny as ‘the new guy’. I feared that any misstep would make my integration into the group a lot harder. I read up on basic class structures, on etiquette, on basic terminology and I even did my best to learn a few Japanese phrases in order to thank sensei for his hospitality. Even before taking a single class I already had a mental image of kendo as very strict, disciplined and unforgiving and I was making assumptions and having worries left and right.

I have now practiced kendo for little over two years and I have found that it is a great tool in conquering my anxiety disorder.

- I experience kendo as a physically tough activity. Seeing myself break through my limitations forces me to reassess what I am and am not capable of.

- The discipline in class feels like a solid wall holding me up and there is a sense of camaraderie. My sempai and sensei will not let me fail and I have a responsibility towards them to tough it out.

- Reading and learning about kendo provides me with confidence that I may one day grow into a sempai role.

- In kendo one aims for kigurai. As Geoff Salmon-sensei once wrote: “kigurai can mean confidence, grace, the ability to dominate your opponent through strength of character. Kigurai can also be seen as fearlessness or a high level of internal energy. What it is not, is posturing, self congratulating or show-boating“. (Salmon, 2009) Thus kigurai is a very empowering concept!

- Kendo is such an engaging activity that it grabs my full attention. Once we have started I no longer have time to worry about anything outside of the dojo. Or as one sempai says: “At tournaments I’m panicking all the way to the shiaijo, but once shiai starts I’m in the zone.“

In the dojo I may forget about the outside world, but there are many reasons for anxiety in the training hall as well. For example, after a particularly heavy training I will feel nauseous and lightheaded, which has led to fears of fainting and hyperventilation. I have also worried about sensei’s expectations regarding my performance and attendance to tournaments (“What if I can’t attend? What will he say? Will he reproach me? Will he think less of me?“).

I have also felt anxious about training at our dojo’s main hall, simply because their level is so much higher than mine. I felt that I was imposing on them, that I was burdening them with my bad kendo and that I was making a fool of myself. I finally broke through this by exposure: by attending a national level training and sparring with 7-dan teachers I learned that a huge difference in skill levels is nothing to be ashamed of. All of a sudden I felt equal to my sempai, not as a kendoka but as a human being.

Another great example of exposure was a little trick pulled by the sensei of our main dojo who is aware of my GAD. He had noticed that I allow myself to bow out early if I start to get anxious. So what does he do? We started class using mawari geiko (where the whole group rotates to switch partners) and right before it’s my turn to move to the kakarite side he freezes the group’s rotation. So now I’m stuck in a position where I have responsibility towards my sempai, because without me in this spot the opposing kakarite would need to skip a round of practice! On the one hand I was starting to get anxious from physical exhaustion, but on the other hand I would not allow myself to stop because of this sense of responsibility. His trick worked and I pulled through with stronger confidence.

In the dojo I regularly use two of the tools taught to me during CBT (Boeijen, 2007):

- Breathing exercises. They let me catch my breath and force me to focus my thoughts on one thing. You breathe in to the count of four, hold it for the two counts, and then breathe out to the count of five. Hold to the count of two and repeat. This exercise is also often used with hyperventilation issues. Various sources, including Paul Budden (Budden, 2007) suggest breathing through the nose instead of the mouth, to prevent over-breathing.

- Relaxation exercises. I scan my whole body for tense muscles in order to release them. For different sections of your body you will tighten up all the muscles up for a few seconds and then release them, which is repeated three times. You start with the facial muscles, making a scrunched up face and releasing it. Then the muscles in the neck. Then the left arm. The right arm. The torso. The buttocks. The left leg. The right leg. When moving to a new section, the previously exercised sections should stay relaxed and in the end you should end up with a completely relaxed body. This exercise is best done while sitting on a chair or bench.

GAD in the dojo, for teachers

If one of your students approaches you about their anxiety disorder, please take them seriously. As I explained at the beginning of this article we all feel fear and have doubts, but an actual disorder is another kettle of fish. You will not be expected to be their therapist or their caretaker; all they need is your support. Simply knowing that you’ve got their back is a tremendous help to them!

In issue #5.2 of “Kendo World” magazine, Ben Sheppard in his article “Teaching kendo to children” (Sheppard, 2010) discusses the concept of duty of care. While the legal aspects of the article pertain to minors in certain countries, the general concept can be applied to any student who may require special care. It would be prudent to have some file containing relevant medical and emergency information. This should not be a medical file by any means, but having a list of known risks as well as emergency contact information would be a good idea.

Please realize that you are helping your student cope with their anxieties simply by teaching him kendo. Brad Binder offers (Binder, 2007) that most studies agree that the regular participation in a martial art “cultivates decreases in hostility, anger, and feeling vulnerable to attack. They also lead to more easygoing and warmhearted individuals and increases in self-confidence, self-esteem and self-control.” This may in part be due to the fact that “Asian martial arts have traditionally emphasized self-knowledge, self-improvement, and self-control. Unlike Western sports, Asian martial arts usually: teach self-defense, involve philosophical and ethical teachings to be applied to life, have a high degree of ceremony and ritual, emphasize the integration of mind and body, and have a meditative component.”

Should a student indicate that they are having a panic attack, take them aside. Remove them from class, but don’t leave them alone. Have them sit down on the floor and against a wall to prevent injuries should they faint. Guide them through a breathing exercise, like described in the previous paragraph. Reassure them that they are safe and that, while it feels scary, they will be just fine. Help them dispel illogical anxious thoughts. Funny kendo stories are always great as backup material.

Finally, I would suggest that you keep on challenging these students. Continued exposure, by drawing them outside of their comfort zone, will hopefully help them extend beyond their limitations. Having responsibilities and being physically exhausted can lead to anxiety in these people, but being exposed to them in a supportive environment can also be therapeutic.

GAD in the dojo, for students

If you have GAD, or another anxiety disorder, I think you should first and foremost extend your support structure into the dojo. Inform your sensei of your issues because he has a need to know. As was discussed in an earlier issue (“Kendo World” #5.2, Sheppard, 2010), dojo staff needs to be aware of medical conditions of their students, for the students’ safety. If there’s a chance of you hyperventilating, fainting or having a panic attack during class, they really need to know.

If you are on medication for your anxieties, please also inform your sensei. They don’t necessarily have to know which medication it is, but they need to be made aware of possible side effects. They should also be able to inform emergency personnel if something ever happens to you.

If you feel comfortable enough to do so, confide in at least one sempai about your anxieties. They don’t have to know everything about it, but talking about your thoughts and worries can help you calm down and put things into perspective. They can also take you aside during class if need be, so the rest of class can proceed undisturbed and so you won’t feel like the center of attention.

Being prepared can give you a lot of peace of mind. I bring a first aid kit with me to the dojo that includes a bag to breathe into (for hyperventilation) and some dextrose tablets. I also look up information about the dojo and tournament venues I will be visiting, to know about amenities, locations and such.

If you aren’t already in therapy, I would sincerely suggest CBT. CBT can help you understand your anxiety disorder and it can provide you with numerous tools to cope. Anxiety is not something you’re easily cured of, but by having the right skills under your belt you can definitely make life a lot easier for yourself!

And let me just say: kudos to you! You’ve already faced your anxieties and crossed your own boundaries by joining a kendo dojo! The toughest, loudest and smelliest martial art I know!

Footnotes and references

1: DSM-IV-TR is Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision. A document published by the American Psychiatric Association that attempts to standardize the documentation and classification of mental disorders.

Binder, B (1999,2007) “Psychosocial Benefits of the Martial Arts: Myth or Reality?”

Boeijen, C. van (2007) “Begeleide Zelfhulp – overwinnen van angstklachten”

Budden, P. (2007) “Buteyko and kendo: my personal experience, 2007”

Buyens, G. (2012) “Glossary related to BUDO and KOBUDO”

Krahulik, M. (2008) “Dear Diary”

Rowney, Hermida, Malone (2012) “Anxiety disorders”

Salmon, G. (2009) “Kigurai”

Sheppard, B (2010) “Teaching kendo to children” – Appeared in Kendo World 5.2

Sluyter, T. (2011) “Dissection of a panic attack”

This article appeared before in Kendo World magazine, vol 6-4, 2013 (eBook and print version on Amazon). The article is republished here with permission of the publisher.

Leven met shikai: gegeneraliseerd angst stoornis en kendo

Het behoud van heijoshin (een kalme, evenwichtige geest) is één van de hogere doelen in kendo.

“Heijoshin weerspiegelt een kalme geestesgesteldheid ondanks verontrustende gebeurtenissen om je heen. [Het] is een gemoedstoestand waar men naar moet streven, in contrast met de shikai, de vier te vermijden toestanden:

- Kyo: verbazing

- Ku: angst

- Gi: twijfel

- Waku: verwarring“

(Buyens, 2012)

In de volgende pagina’s wil ik de lezer graag introduceren tot het concept van de gegeneraliseerde angststoornis, hierna aangeduid als “GAS”. Voor mensen die lijden aan GAS is elke dag gevuld met twee van deze shikai: angst en twijfel. Hoewel ik maar een leek ben, hoop ik dat mijn persoonlijke ervaringen van hulp kunnen zijn voor andere kendoka met het zelfde probleem. Ik zal beginnen met een korte uitleg van de medische achtergrond van GAS, gevolgd door mijn persoonlijke ervaringen. Het artikel wordt afgesloten met suggesties aan leraren en leerlingen in de dojo.

Angststoornissen: definitie en behandeling

Wij zijn allen bekend met de verschijnselen spanning en angst omdat zij normale functies zijn van het menselijk lichaam. Je schrikt van een hard geluid, je springt weg van een bijtende hond en je voelt de druk die je tegenstander uitvoert in shiai. Dit soort dingen bereiden je lichaam voor op wat de “vecht of vlucht” reactie heet: of je rent voor je leven, of je verzet je met hand en tand. Deze instincten worden echter problematisch wanneer zij zonder redelijke stimulus optreden. De beroemdste soorten van dit soort angsten zijn fobieën: de angst voor specifieke objecten of situaties, waar schijnbaar ~25% van de volwassen Amerikanen last van hebben. (Rowney, Hermida, Malone, 2012)

Andere soorten angststoornissen zijn bijvoorbeeld:

- Acute Stress Stoornis

- Agorafobie

- Gegeneraliseerde Angst Stoornis [GAS]

- Obsessieve-Compulsieve Stoornis [OCS]

- Paniek Stoornis

- Post-traumatisch Stress Syndroom [PTSS]

Dit artikel behandelt die stoornis waar ik zelf ervaring mee heb, de gegeneraliseerde angst stoornis.

Misschien is het gemakkelijk om GAS met een analogie te beschrijven: GAS verhoudt zich tot zorgen, zoals een depressie zich verhoudt tot neerslachtigheid. Net zoals een depressief persoon zich “er niet eventjes overheen zet”, zo leeft een persoon met GAS met onaflatende zorgen. Striptekenaar Mike Krahulik beschreef het eens als volgt:

“De bijsluiter van mijn nieuwe medicijnen zegt dat het duizeligheid kan veroorzaken. […] Ik heb daar de hele middag geobsedeerd aan gedacht: ik rijd vandaag zelf naar kantoor, kan ik nog wel naar huis rijden? Wat als ik dat niet kan? Hoe weet ik of ik het niet kan? Moet ik een dokter bellen als ik duizelig wordt? Hoe duizelig is te duizelig? Wat als de dokter er niet is? Moet ik naar het ziekenhuis? Moet ik iemand om een lift vragen? Ik kan m’n auto niet de hele nacht hier laten! De parkeergarage sluit om zes uur, wat moet ik dan met mijn auto? Wat als Kara me niet kan ophalen? Moet ik Kiko om een rit vragen? Als ik duizelig wordt, betekent dat dan dat het medicijn werkt? Of betekent het dat het niet werkt? Wat als mijn medicijn niet werkt?” (Krahulik, 2008)

Als ik parafraseer uit DSM-IV-TR (voetnoot 1) en uit Rowney, Hermida, Malone, dan zijn de criteria voor GAS dat iemand langer dan zes maanden, meer dan 50% van de tijd moeite heeft om zijn zorgen te beheersen en daarbij angstig is voor verschillende evenementen. Deze zorgen moeten niet aanwijsbaar gebonden zijn aan een specifieke angst of fobie en moeten niet voortkomen uit middelenmisbruik. De persoon vertoont minstens drie van de volgende symptomen: rusteloosheid, vermoeidheid, concentratieproblemen, prikkelbaarheid, spierspanning en een verstoord slaapritme.

De symptomen verschillen per persoon, evenals de hevigheid van de ervaren episodes. Zware GAS episodes kunnen leiden tot een paniekaanval, wat je kan beschrijven als tien minuten super-angst. Effecten van een paniek aanval zijn onder andere hartkloppingen, koud zweet, spasmen en kramp, duizeligheid, verwarring, agressiviteit en hyperventilatie. Vanwege deze effecten kunnen mensen met een paniekaanval denken dat ze een hartaanval hebben, of dat ze gewoonweg compleet gek worden.

Een belangrijk element van GAS is het sneeuwbal effect. Zoals mijn therapie werkboek het beschrijft (Boeijen, 2007): een gevoel van angst leidt tot fysieke en mentale uitdrukkingen, die op hun beurt leiden tot angstgedachten. Mensen met GAS zijn vaak bang voor de gevolgen van een angstaanval, zoals flauw vallen of overgeven. Deze angstgedachten leiden tot vernieuwde angst die de ervaren gevolgen weer zullen versterken. En zo voorts. Zo kan zelfs de kleinste twijfel een angstaanval uitlokken. Wat begint met “Dat broodje haring smaakte wat vreemd” kan eindigen met “Oh God ik heb een hartaanval!“. Als je vindt dat dit maar onlogisch klinkt, dan heb je helemaal gelijk! Het sneeuwbal effect voedt zich met aannames, zorgen en twijfels die zich bollen tot een chaotische kluwen. Later volgt nog een voorbeeld.

Behandeling van GAS gebeurt op verschillende manieren, vaak gecombineerd:

- Medische behandeling van reeds bestaande fysieke of mentale problemen.

- Medicinale behandeling van de angst met bijvoorbeeld Prozac, Zoloft, Valium of Ativan.

- Psychotherapie.

- Ondersteuning vanuit de familie en vriendenkring.

Alle geraadpleegde bronnen zijn het eens dat het krijgen van steun van familie en vrienden onmisbaar is voor mensen die lijden aan een angststoornis. Alleen al het feit dat je weet dat er mensen zijn die begrijpen wat je doormaakt geeft de patiënt een stuk houvast. Weten dat deze mensen je zullen vangen als je valt is een steun in de rug. Iemand die jouw onlogische gedachten en twijfels ontward is van onschatbare waarde.

Mijn persoonlijke ervaringen met GAS

Ik heb het geluk dat ik lijd aan maar een lichte vorm van GAS. In mijn hele leven heb ik minder dan twintig echte paniekaanvallen gehad. Waar anderen elke dag, de hele dag in angst leven komt het bij mij alleen in bepaalde situaties naar boven. Voorheen is de diagnose nooit officieel gesteld, maar achteraf beschouwd loop ik al sinds mijn jonge kinderjaren met GAS rond. Toentertijd werden de verschillende symptomen toegedicht aan “schoolziekte”, aan prikkelbare darm syndroom en aan werk-gerelateerde stress. Het was pas tijdens een vakantie in Engeland, in 2010, dat ik door kreeg dat er iets veel groters aan de hand was toen ik een reusachtige paniekaanval kreeg. Ik was enorm geïrriteerd, kon geen samenhangende gedachten meer vormen en twistziek en agressief. Mijn conclusie op dat moment was dat “ik word gek, dat moet’t zijn! Ik heb een pil nodig om dit nu meteen weg te halen!” Vreemd genoeg schoof ik dat alles bij thuiskomst weer weg en besloot ik pas na een tweede paniekaanval om met een professional te gaan praten.

Deze tweede aanval verliep als volgt:

- 13:10: Ik stap het kantoor uit om naar een winkel te gaan, in een deel van de stad dat ik niet ken.

- 13:11: “Hoe zou het met m’n dochter’s buikgriep gaan? Ze was zo naar ziek vanochtend.“

- 13:12: Mijn buik rommelt zeer merkbaar.

- 13:13: “Man, het zou rot zijn als ik ook buikgriep zou krijgen.“

- 13:15: “Wacht, wat als ik het nu al heb? Ik wil niet kotsend over straat!“

- 13:20: “Stik! Die winkel is verder dan ik dacht! Het zou net om de hoek zijn!“

- 13:21: Ik word misselijk en voel me wat bevreesd.

- 13:22: “Misschien moet ik maar terug gaan, ik geloof dat ik in paniek raak. Nee! Ik moet dit overwinnen!“

- 13:25: Ik bereik de winkel en wacht op mijn bestelling.

- 13:27: Mijn paniek wordt erger naar mate ik wacht en ik krijg sterke buikkrampen.

- 13:28: Ik mag niet naar het toilet van de winkel. Ik begin te hyperventileren en hurk op de grond.

- 13:30: Ik betaal en verlaat de winkel. Het dichtslaan van de deur neemt een last van mijn schouders.

- 13:33: Ik voel me opgelucht, maar heb nog steeds hevige krampen.

- 13:50: Ik kom uitgeput en rillerig aan op kantoor. De paniekaanval is over.

(Sluyter, 2011)

Dit illustreert het eerder genoemde sneeuwbal effect: een onschadelijke gedachte (“Hoe zou het met m’n dochter zijn?“) leidt me tot twijfels dat ik zelf ook ziek ben, waardoor ik twijfel over mijn reis door de stad, waardoor ik buikkramp krijg, waardoor ik echt denk dat ik ziek ben, waardoor ik misselijk en duizelig wordt, en zo voorts. Zorgen uitten zich, wat angst schept, wat de eerdere zorgen versterkt. Al met al had mijn huisarts niet lang nodig om me naar een therapeut te verwijzen, voor Cognitieve Gedragstherapy, of “CGT”.

CGT is één van de mogelijke therapieën die van toepassing is op angststoornissen en wordt vaak aangemerkt als de meest effectieve. Er wordt gezegd (Rowney, Hermida, Malone, 2012) dat CGT “een respons behaalt bij 78% van de patiënten die zich toeleggen op 12 tot 15 weken therapie“. Zoals ik het zelf heb begrepen ligt de kracht van CGT in verzelfstandiging: de patiënt wordt opgeleid over zijn stoornis en leert zodoende er mee om te gaan. Men leert symptomen en patronen te herkennen en ook hoe daar mee om gegaan kan worden. Men krijgt hulpmiddelen en handreikingen om episodes te voorkomen, of om te ontspannen tijdens een aanval. CGT berust ook op het principe van ‘exposure’, ‘blootstelling’, waar men continu wordt uitgedaagd om over de eigen grenzen heen te stappen. Dergelijke oefeningen versterken de gevoelens van eigenwaarde en zelfvertrouwen. De wereld wordt een stuk groter dan je eerder zelf toestond.

Het ontkrachten van panische gedachten is de beste manier om de sneeuwbal af te breken. Ze beginnen doorgaans erg klein, waarna ze steeds onredelijker en onzinniger worden. Door elke gedachte direct aan te pakken en logisch af te handelen behoud ik controle. Het is daarbij erg handig om te spiegelen aan een tweede persoon, die als objectieve partij vragen kan beantwoorden. In dat opzicht zijn mijn vrouw en mijn vrienden onmisbaar geworden. Zij helpen mij de onzin uit m’n hoofd te praten.

Ik ben in januari van 2011 begonnen met kendo, een half jaar voordat ik met CGT begon. Ik de week voor mijn eerste les verslond ik online informatie, zodat ik maar geen flater zou slaan. Op voorhand had ik al aannames gemaakt over de dojo: als de ‘newbie’ zou ik constant in de gaten worden gehouden en ik vreesde dat elke misstap het moeilijker zou maken om uiteindelijk in de groep te integreren. Ik las dus hoe een les normaal verloopt, ik las over etiquette, ik leerde basistermen en ik deed zelfs mijn best een paar Japanse dankwoorden te leren om sensei te bedanken voor de gastvrijheid. Voordat ik nog maar één les had genomen zat mijn hoofd al vol met aannames en zorgen over kendo.

Ik doe nu [voorjaar 2013] iets langer dan twee jaar aan kendo en ik heb het ervaren als een grote hulp in het overwinnen van mijn angststoornis.

- Ik ervaar kendo als een fysiek zware activiteit. Telkens wanneer ik mijn grenzen opzoek wordt ik gedwongen om mijn eigen mogelijkheden te heroverwegen.

- De discipline in de dojo is als een stevige muur die me rechtop houdt en in de les is er een gevoel van kameraadschap. Mijn sempai en sensei laten me niet zomaar zakken en ik heb een verantwoordelijkheid naar hen toe om door te zetten.

- Het vele lezen en leren dat ik doe ter ondersteuning van mijn leergang geeft me het vertrouwen dat ik ooit ook door kan groeien naar een sempai rol.

- In kendo streeft men naar kigurai. Geoff Salmon-sensei schreef ooit: “kigurai kan zelfvertrouwen betekenen, gratie en de mogelijkheid je tegenstander de baas te zijn door de kracht van je karakter. Kigurai kan ook worden gezien als onbevreesdheid of een enorme hoeveelheid interne energie. Wat het niet is, is overdrijven, jezelf schouderklopjes geven en in het voetlicht willen staan“. (Salmon, 2009) Kigurai is een versterkende eigenschap!

- Kendo grijpt me bij me kladden en laat me niet los. Als de training begint heb ik geen tijd meer om na te denken over wat er zich buiten de dojo afspeelt. Zoals één sempai ooit zei: “Op toernooien vreet ik mezelf helemaal op tot aan de rand van de shiaijo, maar als de shiai begint ben ik helemaal in-the-zone.“

In de dojo vergeet ik misschien wel wat er in de buitenwereld gebeurt, maar ook tijdens les zijn er genoeg dingen waar angsten door kunnen ontstaan. Zo kan ik na een zware training misselijk en lichthoofdig worden, wat heel normaal is. Helaas kan het bij mij leiden tot de vrees dat ik flauw ga vallen, of ga hyperventileren, of dat ik met m’n men nog op boven de prullenbak moet hangen. Op zijn beurt leidt dat weer tot de gedachte “Wat zouden mijn sempai daar van denken?!“. Ik heb me ook zorgen gemaakt over sensei’s verwachtingen over mijn inzet en mijn deelname aan toernooien (“Wat als ik niet mee kan doen? Wat zou hij daar van vinden? Zal hij me verwijten? Zal hij een prutser vinden?“).

Ik voelde me zelfs angstig over het trainen in de hoofd-dojo van onze vereniging, puur omdat het niveau daar zo veel hoger ligt dan het mijne. Ik had het gevoel ze maar tot last te zijn met mijn slechte kendo en dat ik me als een idioot zou gedragen. Uiteindelijk was het een kwestie van ‘exposure’: door aan een Centrale Training deel te nemen en te sparren met een zevende dan-er leerde ik dat een groot verschil in vaardigheid niet iets is om je voor te schamen. Plotseling voelde ik mij als een gelijke met mijn sempai, niet als kendoka maar als mens.

Een ander mooi voorbeeld van ‘exposure’ was een truc die sensei (die van mijn GAS afweet) met me uithaalde. Hij had al gauw door dat ik soms wel erg vroeg uit de rij stapte omdat ik nerveus werd. Dus wat deed hij? We begonnen de les met mawari geiko (de hele groep roteert om steeds van partner te wisselen) en vlak voordat ik naar de kakarite kant zou oversteken zet hij de rotatie op slot. Ik moest aan de motodachi kant blijven staan, waardoor ik plots een extra verantwoordelijkheid kreeg: als ik nu zou stoppen, kon een hele groep kakarite niet meer oefenen. Aan de ene kant was ik al nerveus van de vermoeidheid, maar aan de andere kant wilde ik mezelf niet toestaan om nu te stoppen. Sensei‘s trucje werkte.

In de dojo gebruik ik regelmatig twee hulpmiddelen die ik bij CGT heb geleerd (Boeijen, 2007):

- Ademhalingsoefeningen. Ze stellen me in staat even op adem te komen en ze dwingen mij om mijn gedachten op iets anders te richten. Je ademt in voor vier tellen, houdt het voor twee tellen vast en ademt dan voor vijf tellen uit. Houdt het weer voor twee tellen vast en herhaal het patroon daarna weer. Deze oefening wordt vaak ingezet bij hyperventilatie. Verschillende bronnen, waar onder Paul Budden (Budden, 2007) suggereren dat men het beste kan ademen door de neus in plaats van de mond om zo te voorkomen dat er te veel of te snel wordt geademd.

- Ontspanningsoefeningen. Ik speur mijn lichaam van top tot teen af, op zoek naar gespannen spieren. Achtereenvolgend worden er verschillende spieren drie keer, kort heel strak aangespannen en weer los gelaten. Je begint met het gezicht, gevolgd door nek, de linker arm, de rechter arm, het bovenlijf, de billen, het linker been en het rechter been. Wanneer je met een stel spieren verder gaat moeten alle voorgaande spieren ontspannen blijven en uiteindelijk heb je zo een ontspannen lichaam. Deze oefening kan het beste op een stoel (of een bank op de zijlijn) worden gedaan.

GAS in de dojo, voor leraren en sempai

Word je ooit door een leerling benaderd over zijn angststoornis, neem hem/haar dan alsjeblieft serieus. We hebben allemaal angsten en twijfels, maar een stoornis is toch andere koek. Men zal niet van je verwachten dat je voor therapeut speelt of dat je hulpgever wordt; het enige dat ze nodig hebben is je steun. Als ze weten dat je voor ze klaar staat is dat een enorme hulp!

In vol. #5.2 van “Kendo World” besprak Ben Sheppard in zijn artikel “Teaching kendo to children” (Sheppard, 2010) het concept van “zorgplicht”. Hoewel het artikel gaat om de wettelijke verplichtingen jegens minderjarigen in specifieke landen, kan het algemene concept worden toegepats op elke leerling die speciale zorg vereist. Het is raadzaam om een overzicht te hebben van deze leerlingen, met relevante medische informatie en contactgegevens. Dit is geenszins een medisch dossier, maar eerder een lijst van bekende risico’s en korte instructies. Zo weten de leraren en begeleiders hoe er gehandeld moet worden als een leerling in de problemen zit (denk ook aan epilepsie, diabetes, e.d.).

Wees je alsjeblieft bewust dat je jouw leerling helpt omgaan met zijn stoornis door hem kendo te leren. Brad Binder stelt (Binder, 2007) dat de meeste studies het eens zijn dat deelnemen aan een vechtsport “een afname in vijandigheid, woede en kwetsbaarheid cultiveert. Het leidt ook tot meer ontspannen en vriendelijkere individuen en bouwt zelfvertrouwen, eigenwaarde en zelfbeheersing.” Dit kan ten dele komen doordat “Aziatische vechtsporten traditioneel nadruk leggen op zelfkennis, zelfverbetering en zelfbeheersing. In tegenstelling tot westerse sporten, leren Aziatische vechtsporten doorgaans zelfverdediging, filosofie en ethiek. Zij hebben een hoog ceremonieel gehalte, benadrukken de integratie van lichaam en geest en hebben vaak een meditatief element.”

Geeft een leerling aan dat hij een paniekaanval heeft, neem hem dan terzijde. Heel hem uit de les, maar laat hem niet alleen weg gaan. Laat hem tegen een muur zitten voor stabiliteit en praat wat met hem. Herinner hem aan zijn ademhalingsoefeningen. Bevestig dat hij gewoon veilig is en dat, hoewel het eng is, alles gewoon goed komt. Als er onlogische angstgedachten zijn, rationaliseer die dan. Een leuk, afleidend kendo-verhaal valt ook vaak in goede aarde.

Ter afsluiting zou ik voorstellen dat je deze leerlingen blijft uitdagen. Herhaalde blootstelling bouwt zelfvertrouwen, haal ze uit hun comfort zone en help ze zo hun grenzen te doorbreken. Het hebben van verantwoordelijkheden en het ervaren van fysieke uitputting kan beangstigend zijn, maar door dit vaker mee te maken in een veilige omgeving kunnen zij enorm groeien.

GAS in de dojo, voor leerlingen

Als je aan GAS, of een andere angststoornis leidt, dan denk ik dat je allereerst ondersteuning moet zoeken binnen de dojo. Informeer op zijn minst je leraren, omdat zij op de hoogte moeten zijn als er iets echt mis gaat. Als er een kans is dat je gaat hyperventileren of flauw vallen, dan moeten zij daar op voorbereid zijn.

Gebruik je medicatie, informeer je leraar dan. Hij hoeft niet persé te weten wat je slikt, maar hij moet op zijn minst de bijwerkingen kennen en weten van de toediening. Dit soort informatie is ook erg nuttig voor hulppersoneel, mocht er een noodgeval zijn.

Voel je je daar goed genoeg bij, neem dan op zijn minst één sempai in vertrouwen. Ze hoeven niet alles te weten, maar het is voor jou prettig als je met hem/haar kan praten als je angstgedachten ervaart. Zo heb je ook in de dojo een rationele, tweede partij die je gedachten kan kalmeren. Deze persoon kan je bij de les terzijde nemen, zodat je niet het gevoel hebt de hele les te verstoren.

Voorbereiding kan je veel gemoedsrust geven. Ik heb zelf altijd een EHBO setje bij me, met onder andere een zakje om te ademen (bij hyperventilatie) en een set dextrose tabletten. Als ik voor een toernooi of CT naar een nieuwe locatie moet, dan zoek ik ook eerst altijd op hoe het gebouw er uit ziet en waar de verschillende voorzieningen (toiletten, kleedkamers) zich bevinden.

Loop je nog niet bij een therapeut, dan kan ik CGT van harte aanraden. CGT kan je helpen je stoornis te begrijpen en het kan je hulpmiddelen geven om er mee om te gaan. Een angststoornis is niet, of maar moeilijk, te genezen, maar met de juiste vaardigheden ben je in staat je leven een stuk gemakkelijker te maken.

En laat me je feliciteren! Want je hebt je angsten in de ogen gekeken en je grenzen overschreden door bij een kendo dojo te gaan. Het is de zwaarste, luidste en stinkendste vechtsport die ik ken!

Voetnoten en referenties

1: DSM-IV-TR is een diagnostische en statistische handleiding voor geestelijke stoornissen. Het is een document van de American Psychiatric Association die poogt om de documentatie en classificatie van geestesziekten te standaardiseren.

Binder, B (1999,2007) “Psychosocial Benefits of the Martial Arts: Myth or Reality?”

Boeijen, C. van (2007) “Begeleide Zelfhulp – overwinnen van angstklachten”

Budden, P. (2007) “Buteyko and kendo: my personal experience, 2007”

Buyens, G. (2012) “Glossary related to BUDO and KOBUDO”

Krahulik, M. (2008) “Dear Diary”

Rowney, Hermida, Malone (2012) “Anxiety disorders”

Salmon, G. (2009) “Kigurai”

Sheppard, B (2010) “Teaching kendo to children” – Appeared in Kendo World 5.2

Sluyter, T. (2011) “Dissection of a panic attack”

Dit artikel verscheen eerder in het tijdschrift Kendo World, vol 6-4, 2013 (eBook en drukwerk beschikbaar op Amazon). Het artikel is hier opnieuw gepubliceerd met toestemming van de uitgever.

On Saturday the 26th of April there will be NO training. Not in Amstelveen and not in Almere. This is due to the national holiday King’s Day.

On Saturday the 26th of April there will be NO training. Not in Amstelveen and not in Almere. This is due to the national holiday King’s Day.